Photo Essey

-

Field landscape in Kazakhstan

Buho HOSHINO (Rakuno Gakuen University)

Camel Brands of the Mongolian Pastoralists

Solongga

(Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Chiba University)

In Mongolia pastoral society, pastoralists have the customs to make marks on the livestock that they own. They make cuts in the ears of livestock, brand mark on the epidermis of the body part, apply of paint to the hair and horns, and make notches on the horns. What’s more, sometimes it will be used as a possession signed by attaching a personal mark by tools used for livestock. In Inner Mongolia, there are also some pastoral areas with customs to mark livestock.

I did a field survey by interviewing in Badain Jaran Desert, Alsha Right Banner, Inner Mongolia, by March, 2017, September, 2018. The subject of the survey is Mr. Su, who is a camel pastoralist. In field survey area, there is a custom of branding marks on camels.

Brand-mark is a mark which the Mongols called as Tamaga. The pastoralists only must give their camels the mark which is not the same as anyone else’s to show his ownership.

Camel branding is a technique for marking camel to identify their owner. Pastoralist brand the camel on the flank, upper buttocks and cheeks, which is often branded to left side. The location where the mark was branded by each pastoralist is also different. There is also the branded mark on one place, and there are two ones as well. During the field of survey, Mr. Su's mentioned that brand mark was a brand name of Shirettai Atabchi and Nuden Hѳѳreg which were branded to two places. When branding a mark, they use a steel iron.

In addition to this, they use owning markings such as painting a camel, marking the ears, hanging a string called Duujin on the neck.

Photo1.Brand mark to camel's

Photo1.Brand mark to camel's Photo2. Brand -mark of Shiretai

Atabchi

Photo2. Brand -mark of Shiretai

Atabchi Photo3. Brand mark to camel's left flank

Photo3. Brand mark to camel's left flank

Photo4. Brand -mark of

Nuden Hѳѳreg

Photo4. Brand -mark of

Nuden Hѳѳreg

Photo5. Painted camel

Photo5. Painted camel Photo6. Ear marks made of red cloth

Photo6. Ear marks made of red cloth

Photo7. “Duujin” which will be put on the neck of camels

Photo Essay on my field workAkifumi SHIOYA (University of Tsukuba)

Photo 1. Lunch with Dr Kamiljan Khudayberganov (Senior Researcher, State Museum-Reserve Ichan-Kala) and Dr Alisher Khaliyarov (PhD Candidate, Ohio State University).

Photo 2. Interview with a local historian in Urgench, Republic of Uzbekistan. Urgench was the biggest commercial city in Khorazm region in the nineteenth and the beginning of twentieth cen- turies.

Photo 3. View of Tatarskaia sloboda (old Tatar settlement) in Kazan, Russia. The merchants from this settlement stretched their commercial network in the Eurasian continent.

Photo 4. Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi istoricheskii arkhiv (Russian State Historical Archive). The rich collection of the records regarding the Russo-Central Asian trade attracts researchers to work in the archive.

Photo Essay on my field workShogo KUME

(Tokyo University of the Arts)

Photo 1 Modern Naryn city is located at an altitude of 2000 m a.s.l. in central Kyrgyzstan, stretch- ing roughly 15 km from east to west in the narrow river valley of Naryn. Several ancient burial grounds are also situated on the banks of the river.

Photo 2 General view of an ancient pastoralist settlement of Mol Bulak 1 in September 2018, looking southeast. The site is located at an altitude of 2400 m a.s.l. in the Naryn-Too mountain range of the Inner Tien Shan, which lies immediately southeast of the modern city of Naryn.

Photo 3 Excavations at Sector 1 of Mol Bulak 1. Over two thousand years’ continuous occupa- tional sequence by ancient pastoralists has been revealed by two seasons’ excavations at the site.

Photo 4 (b)

Photo 4 (a)

Photo 4 Modern pastoralist occupation around Mol Bulak 1: a winter camp of a modern pastoralist family near Mol Bulak 1. Horticultural crops like potatoes are also cultivated around the camp (a); free-ranging horses spread on the slope in the mountains near the camp (b).

Camels in Ejene district, Inner Mongolia, China

KODAMA, Kanako

(Chiba University)

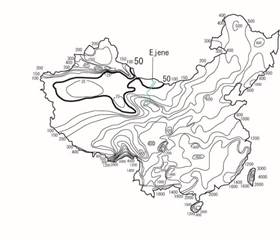

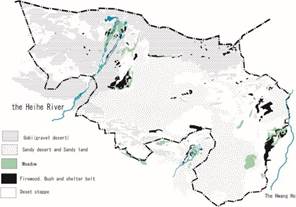

One of the field places is Ejene (Ejina) banner, Inner Mongolia, China. Ejene district has little rain, only 39mm per year, and locates in the aridest district in China (Fig.1). However, because Ejene district locates in a relative lowland area, snowfall and rainfall in the Qilian mountains flow into Ejene, forming the Heihe River. Therefore, the landscape of Ejene consists of meadows, firewood, bush, and shelterbelts along a river flowing through the Gobi desert (Fig.2). The Heihe River forms an oasis in Ejene district (photo.2; Photo 1-3). Oasis mainly consists of Populus euphratica and Tamarix tenuissima, which are both excellent feed for camels. Also, the gobi desert is suitable for camels (photo. 4-6). These camels are all Bactrian camels.

Fig.1. Anuual Precipitaion Amout of China

(Edical Committee for Climatologcal Atlass of the People's Republic of China 2002:49)

Fig.2. Land-use map of Alashan league,China

Photo. 1. Oasis (August, 2003)

Photo. 2. A camel in Oasis

(August, 2003)

Photo. 3. A Camel in Oasis

(September, 2003)

Photo. 4. Camels in the Gobi

(September, 2003)

Photo 5. Camels in the Gobi

(September, 2003)

Photo 6. Camels in the Gobi

(September, 2003)

Essay on my field work

SAITOU Naruya

(National Institute of Genetics)

“Saito!” Phone from Anna started from this word, when I got her phone call at my hotel room in Astana, capital of Kazakstan. Early next morning, Anna and other people brought me to Astana Airport, and we met Professor

Imamura Kaoru, who just came from Japan. We then had breakfast in Astana. Prof (Central Asian style fried rice) was

splendid! We met Dr. Prof. Victor Zaibert after breakfast, and headed to Botay archeological site.

On this way, Dr. Zaibert introduced us reconstructed Botay houses. Photo 1 is

outside view, and photo 2 is inside view.

Photo1

Photo1

Photo2

Photo2

This reconstruction was directed by Dr.Zaibert, and he hopes that this place will become much larger national archeological park in future. After several hours of driving, we arrived at Botay excavation camp near Botay site. So many horse bones were excavated from this site, so many horse bones were just thrown away to edge of camp (photo 3).

Photo3

Photo3

Photo 4 shows something. Can you guess function of this tube-structure? It is dining room! Photo 5 shows breakfast time there, and Prof. Imamura, Anna, and Dr. Zaibert are chatting there.

Photo4

Photo4

Dr. Zaibert asked me to examine ancient DNA of one human bone found in 2017. I am holding part of this human’s jaw in photo 6. We first estimated its age using C14

method, and in fact it was quite

old (more than 4000 years ago). We are going to study its ancient DNA. Photo 5

Photo 5  Photo 6

Photo 6How to assemble a yurt

Kaoru IMAMURA

(Nagoya Gakuin Univeristy)

Kazakh people assemble mobile dwellings (yurts) on pastureland (summer camps) only in the summer. At other times of the year, they live in fixed dwellings made of wood and brick. They carry the yurts from their spring camps to their summer camps, and quickly assemble the yurts at their destination. In the case study I observed on June 13, 2018, they started assembling the yurts at 1 p.m., and had completed their work after three-and-a-half hours, including a 40- minute break for lunch.

The walls of the Kazakh people’s yurts that I introduce here are made of latticed boards that fold into a cylindrical shape (Photo 1, Photo2). When this is laid out, it extends up to 5 m in length. Five of these are used to build a circular wall. The interior of the yurt is a circle reaching approximately 6 m in diameter.

Kazakh pastoralist live in mobile dwellings (yurts) on pastureland (summer camps) only in the summer months. They move from the spring camps to the summer camps, and assemble the yurts according to the following steps:

1. The door (есік)’s position is decided and erected. The entrance is placed at a 90° angle to the direction of the wind to stop it from entering the yurt (Photo 1).

2. The wooden lattice wall (known in Kazakh as кереге) is extended to construct a circular wall (Photo 1).

3. A special cord (кереге бау) is used to tie together and connect the кереге (Photo 4).4. The crown wheel (шаңырақ) is erected using two poles (бақаң). (The бақан are removed after the yurt has been fully assembled.) (Photo 3)

5. A wide cord (жел бау) is extended from the crown wheel to the wall (жел бау meaning“wind cord”) to fix the crown wheel in place.

6. One end of each roof pole (ұық) is inserted into the hole of the crown wheel, and the other is affixed to the wall, forming a roof made from the poles in a radial shape like an umbrella. The roof poles are tied to the walls with a special cord (ұық бау) to secure the roof. (Photo5, Photo 6, Photo 7) Those cords (ұық бау) are made by horse hairs and sheep hairs.

Photo 1 Door(есік) and lattice wall (кереге)

Photo 2 lattice wall (кереге)

Photo 3 Crown wheel (шаңырақ) is erected

using two poles (бақаң)

Photo 4 кереге is tied by кереге бау

Photo 5 A roof pole (ұық)

Photo 6 Roof poles

Photo 7 Roof poles tied to the walls by the rope (ұық бау)

Photo 8 A wide belt-like cord (ішк арқані)is circled around the wall

Photo 9 Sand barriers (ораған ши)

Photo 10 басқур, view from inside7. A wide belt-like cord (ішк арқані)is circled around the wall to fasten and secure the entirewall (Photo 8).

8. Sand barriers (ши) (Photo 9) are wrapped around the outside of the wall. The sand barriers are made of reeds and look like rush mats. When making the sand barriers, the patterned sand barriers—made by wreathing colored threads and reeds, then weaving the colorful strands—are called ораған ши.

9. Belts are wrapped around the outside of the roof poles to fasten and secure the roof. The belts made of fabric and are called басқур (Photo 10), while those made of felt are called қарақас. Both types will be copied with the pattern on the inside so one is able to see it when inside the yurt. (Photo 8, Black belt)

10. The wall is wrapped in special wall felt (туырдық) from the outside (Photo 11).

11. Cords (туырдық бау) coming from two corners of the special wall felt are tied over the roof to the top of the wall lattice on the other side to secure it (Photo 13)

12. The roof is covered with roof felt (туырдық узік)(Photo 12).13. The special cords fixed to the corners of the felt (called узік бау, meaning “roof cord”) are rotated around to the counter side of the roof, then draped down the wall to the floor and fastened to the foot of the wall lattice, thus securing the special roof felt.

14. The inner white cloth (ішкі көшкі) is spread across the entire yurt (Photo 14).15. A special cord (ішкі көшкі бау, meaning “inner cloth cord”) is used to secure the white cloth to the lattice walls (кереге) .

16. A plastic sheet (жылтыр қағаз, meaning “plastic paper”) is spread across the roof for waterproofing (Photo 15).

17. A white outer cloth is draped over the entire yurt (сыртқы көшкі, meaning “outercloth”)(Photo 16).

Photo 11 Wall felt (туырдық)

Photo 12 Roof felt (туырдық узік)

Photo 13 Tieing the cords of wall felt

Photo 14 Inner white cloth (ішкі көшкі)

Photo 15 Plastic sheet (жылтыр қағаз)

Photo 16 White outer cloth (сыртқы көшкі)

Photo 17 Two kind of cords are tied

Photo 18 Inside the unfinished yurt

Photo 19 Inside the unfinished yurt

18. A wide cord (сыртқы белдеу, meaning “waistline”) and two thick cords (арқан) are tied around the yurt (Photo 17)

19. A cord coming out of the outer cloth (сыртқы көшкі бау, meaning “outside cloth string”) is fastened to the арқан to secure the outer cloth.

20. Felt covering the crown wheel (тундік, meaning “nighttime thing”) is thrown over the top of the yurt and attached to the crown wheel (Photo 23).21. Four cords extending from the four corners of the тундік бау (тундік бау, meaning “felt string covering the skylight”) are fastened to the wall lattice. Three are fixed and the final one is used for opening and shutting (Photo 22). The тундік is shut at night, then opened in the morning. It works both to maintain warmth and allow light in.

22. The belt cord (кіндік бау, meaning “navel string”)(Photo 22, Photo 24, red belt) fastened to the center of the тундік is fastened and fixed to the wall lattice from inside the yurt.

23. The lower end of the sand barrier (ірге ши) is wrapped around the skirting of the yurt.24. Two thick, strong cords (бастырған арқан, meaning “drawn thick rope”) are fixed to the ground on the left- and right-hand sides of the door, and the thick cords are extended from the front over the roof to the back of the dwelling and the ends tied to rocks. This stops the whole yurt from being blown away by the wind.

Once the yurt was assembled, rugs were hung on the walls, and bedding, clothing, foodstuffs, and cookware were placed in the dwelling. Finally, the stove (пеш) was put in, and water was boiled, and everyone drank tea together at 5 p.m.

Photo 20 Open the sky light

Photo 20 Open the sky light

Photo 21 Inside the yurt

Photo 22 Felt covering the crown

wheel (тундік). 4 cords at the corner and 1 cord in the center.

Photo 23 Putting up the тундік to the top of yurt. Lower sand barriers (ірге ши) are already around

the skiirting of the yurt.

Photo 24 Put the stove and

chimney in the yurt

Photo 25 Lower sand barrier (ірге ши)

Photo 26 Arange the rugs, carpets, bed, bags, chest, and prepare tea time

My Field Work Report 2018

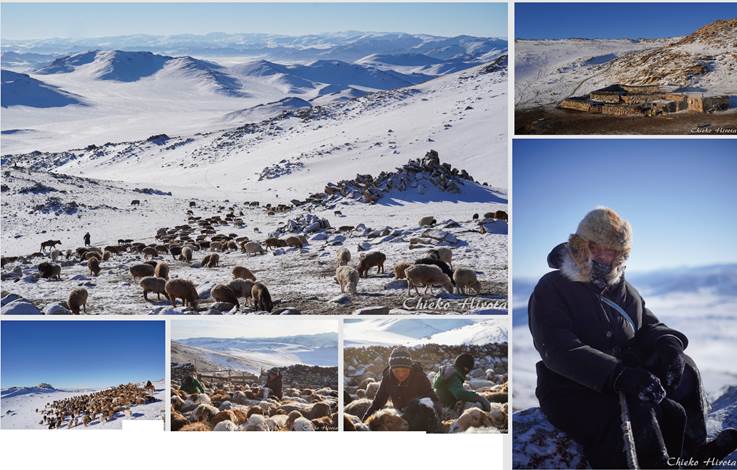

Chieko Hirota(Chiba University,JSPS fellowship researcher DC2)The purose of my research is to demonstrate the way Kazaakhs in Mongolia pass on their culture of ornament and decoration. Kazakh people are scattered around the world,including Kazakhstan,China,Russia,Kirgiz,Turkey and Mongolia.

Kazakhs have sustained and developed their unique culture,while flexibly adapting to the environment they live in,conditioned by the social and economic influences from each country and region. The Kazakhs in Mongolia are still choosing to do animal husbandary as their main livelihood and inherit their culture rooted in nomadism.

To understand the structure that supports the inheritance of omamenting and decorating culture in Mongolian Kazakh society,it is necessary to analyze the social and economic circumstances which they are put in now. Therefore ,this year,1 have focused on the situation of Kazakh pastoralist' s daily life through fieldworks and staying with them at their home in Bayn-Ulgii province,Mongolia.

The research was conducted from July to September,and in December,2018,in Bayn-Ulgii provience,Mongolia. 1 went to 7counties in Bayn-Ulgii during 3monthes. Particularly,1 stayed for a1most two weeks at the home o fMr. Yerjan,who is a pastoralist in Sagsai county, Bayn-Ulgii province. During my stay at Mr. Yerjan' s home,1 did participant observation regarding the way of grazing in summer camp, making livestock products,especially felt and dairy products,and making handcrafts. Also,1 visited winter camp of Mr. Yerjan in December

and recorded their life during winter time.

Through these research,1 have observed the annual flow of Mongolian Kazakh pastoralist' life,the process of making and using stock products,the actual situation of their livelihood and some social and cultural norms in their socity.

One ofthe Kazakh Summer capm/ Astausha/ Sagsai county/ Bayn-Ulgii provience/2018.08

The process of making and using dairy products/ 2018.08

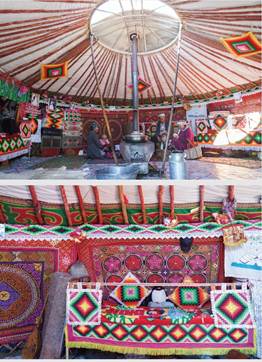

Inside of Kazakh traditional Yurt,called“Ui" / Burgan county/ Bayn-Ulgii province/ 2018.09

Kazakh traditional embroidery by hook,called“Biz Keste" / Burgan county/2018.09

Kazakh weaving,called“Terme" / Sagsai county/2018.07

The process ofmaking felt/ Sagsai county/ Bayn-Ulgii province /2018.08

One of the Kazakh winter camp /Sagsai county/ Bayn-Ulgii province/2018.12 (The person on the right comer of photo is Mr. Yerjan,who is one of my informants)

The Typology of Enclosures and Stalls for Livestock in the Small Aral Sea Region

Tetsuro CHIDA

(Nagoya University of Foreign Studies)

Talgarbay KONYSBAEV

(Kazakh National University)

Preface

Livestock stalls and enclosures are two distinctive features of the settled (or semi-set-

tled)-style livestock breeding. In the Small Aral Sea region, we can see traditional yurts (movable tents) only in auspicious life events for Kazakhs like weddings, circumcision ceremonies and so on, in which a householder has to invite and warmly recieve so many guests. In today’s environ- ment Yurts relate more to the cultural and historical identity of Kazakhs than essentials for ordi- nary life. Instead, we can find various kinds of stalls and enclosures, in which young animals or animals with harsh diseases are kept especially during winter in the harsh climate. Besides, during summer several baby camels are held in corrals for getting camel milk. Basically, camels walk around pasturelands in groups without control by humans, but the mother of an isolated baby comes back to the barn at regular intervals. Women from the community take the milk, when the mother suckles her baby. Horses and cows also move around the villages by themselves in the region without human intervention.

In this short essay, the author would like to give an overview of the typology of enclo- sures and stalls, showing photos taken in Akbasty and Zhalanash villages during field research conducted by the author in August, 2018. Zhalanash Village is located 40 kilometers from Aralsk City, but Akbasty is very remote, located on the southern edge of the Small Aral Sea, 250 kilo- meters from Aralsk. The population of these villages is very small. Akbasty has only 510 residents (on November 1, 2017). Locals in both villages are engaged in fishery as well as livestock breed- ing. The Bactrian camel is the main animal in these settlements, but locals are holding horses, sheep and a small number of cows as well.

Enclosures

Photo 1. Traditional enclosure with shrubs

Photo 1 shows a traditional enclosure in the Small Aral Sea region, using local clays and shrubs such as көкбұта or Calluna vulgaris, тамарикс or Tamarix etc. Quite often sheep feces are mixed in clays to hold warmth inside. Locals constructed these traditional enclosures in the

1970s, when the ecological situation in the region was still not so harsh. All materials originated in the region, and the villagers well considered local atmospheric and ecological conditions when designing the structure of this sort of enclosures.

Photo 2. Traditional enclosure with a high wall

Photo 2 is also the traditional enclosure made by local shrubs, clays and sheep feces, and its wall is very high, at more than two meters. This enclosure is located on the former Aral Sea shore, where herdsmen have to protect their animals from strong winds from the former lake side.

Photo 3. Metallic enclosure made of scrap iron from discarded ships

Photo 3 shows a more modern enclosure made of scrap iron, which locals collected from

discarded ships on the former Aral Sea bed. As is well known, the diminishment of the Aral Sea made navigation of the Aral Sea impossible in 1980s. It seems that the owner enlarged his enclo- sure, bringing scrap irons from somewhere on the former lakebed, after ships and other maritime transportation facilities were abandoned. They constructed this sort of enclosures after the col- lapse of the Soviet Union.

Photo 4. Very metallic modern enclosure made by rolled-out barrel

This type of enclosure is quite new and the structure contains rolled-out metallic drum cans. It looks tidy, but obviously cannot keep warmth inside the enclosure in winter time. Maybe it can withstand strong winds but only partially. As written above, camels and horses in the Small Aral Sea region move around deserts or pasturelands in assemblages without control by humans. Considering that, this type of enclosure is likely to be used only during summertime, and sheep and young animals of other species are kept in the stall during winter season.

Stalls

Photo 5. Traditional, well-structured and clean livestock stall

Photo 5 was taken in one of the best structured and cleanest livestock storage spaces in Akbasty Village. The stall is constructed at the bottom of the excavated slope. Therefore, wind and heat does not go through the structure, which, in turn, can keep a comfortable temperature inside. Wood, clay and reeds are used, and sheep excrement is also blended in the clay wall to keep warmth. The owner of this structure collects sheep excrement for fuel in the kitchen, so the ground is always kept clean. In the authors’ experience, this construction is traditional and typical in the region.

Photo 6. Livestock stall, constructed by woods and bricks

Photo 7. The roof with stretched fishing nets, wood,

weeds and clays in the stall of Photo 6

Photo 6 and 7 is of a well-constructed livestock stall in Zhalanash Village. Sun-dried clay bricks and wood are two main materials used in the construction of the stall, but it is really unique that stretched fishing nets are used to bear the weight of roofing materials (clays and weeds), which shows that villagers are really engaged in both fishery and livestock breeding. Clay bricks are handmade in the village. Coal ashes and water are mixed into local clays.

Photo 8. The livestock stall under construction without rooftop

Photo 9. The high-quality and carefully structured livestock stall under construction

Luckily, the author could see two construction sites of livestock stalls in Akbasty Village during the field work. The first one is still lacking a roof, but walls are well-constructed with clays, bundled weeds, wooden frames and concrete foundations. The second one looks high-quyality and very carefully constructed. Even slates are used as roof materials at the top, as well as clays, weeds and wooden frames are used under the slates. As for walls, we could see layers of wood frames, clays, bundled weeds and lime from inside to outside. Evidently, this kind of stall structure is a mix of the traditional style of stall construction and more modern construction materials. Actually, the owner of the stall of Photo 9 is one of the richest residents in the village.

Photo 10. A modern but functionally deficient stall, using porous shell bricks

The final and most “modern” stall is constructed with shell bricks, which are delivered into the village by tracks from Beineu region in Mangistau Province. The construction looks beau- tiful and neat, but the construction material, shell brick, is porous and low density. Therefore, cold winds during winter will penetrate the stall. Perhaps hot temperatures during summertime can be alleviated thanks to its good ventilation. The material is inexpensive and tidy, but is not suitable for the local atmospheric conditions. Nonetheless, locals like to use this material these days be- cause of its neatness and, more probably, their style of livestock breeding. As written above, peo- ple prefer to leave their animals in wild nature around the village.

Concluding Remarks

Observing the structures of enclosures and stalls, we can understand how locals see the relationship between humans, animals and nature. As written above, villagers had apparently con- sidered local ecological and atmospheric conditions, using local shrubs, weeds, clays and even sheep excrement for their enclosures and stalls. After the collapse of the USSR, they started to use scrap metals, taken from abandoned ships and other waterway traffic facilities. That is, they began to seriously think of economic factors in the market-oriented economic reform as well as harsh ecological conditions after the Aral Sea crisis. Villagers are now using tidy-but-cheap ma- terials like shell bricks or rolled out drum cans for construction, which are not suitable for the climatic and other atmospheric conditions in the region. However, it is still likely that they are concurrently thinking that these materials are enough to keep their way of livestock breeding, where humans usually do not intervene in life of animals, and leave them in wild nature. It is possible that because of the low population, the remoteness of villages and little competition among people as well as animals.